|

September 2025 - MABA Biosolids Spotlight

Provided to MABA members by Bill Toffey, Effluential Synergies, LLC

SPOTLIGHT on the MABA Origin Story

The year 1997 was a tough one for biosolids practitioners on every front. In hindsight, any optimism that might have been felt from the mostly positive findings of the 1996 report by the National Research Council (NRC) titled “Use of Reclaimed Water and Sludge in Food Crop Production” had been offset by many other struggles. The NRC report was weighty, but it was not as attuned to popular culture than had been the 1995 book “Toxic Sludge is Good For You: Lies, Damn Lies and the Public Relations Industry.” This book had pilloried the Water Environment Federation for its 1991 introduction of the new term of “biosolids” and had tagged as greenwashing the US EPA funded Powell Tate communications plan to “sell sludge.” In mid-1997 came the "The Case for Caution: Recommendations for Land Application of Sewage Sludge and an Appraisal of the U.S. EPA's Part 503 Sludge Rules" which enjoyed the imprimatur of the renowned Cornell University, and it was immediately popular with the anti-biosolids activists. “Case for Caution” also stoked new fire under two roundly disputed, but media-charged claims of death-by-biosolids, both allegedly occurring in 1994, of 26-year-old Shayne Conner in New Hampshire and of 11-year-old son Tony Behun in Pennsylvania. These East Coast stories compounded the “deadly deceit” reports coming out of the State of Washington about the Zander farm’s sick cows and farmers. Making matters even worse, David Lewis, a senior EPA microbiologist, had been working within his agency and publicly badmouthing his agency’s new biosolids rules, and articles by Caroline Snyder, a college professor in New Hampshire with a Harvard PhD, reached a national audience to claim scientific malfeasance and cover up. Support for biosolids recycling was on its heels in 1997.

Pushing back against this tide was the “Regional Biosolids Information Networks Workshop: Investing in Success.” Held over a full two days on June 11 and 12, 1997, in Seattle, hosted by biosolids manager Pete Machno, the workshop featured speakers from Metro Seattle and other wastewater agencies, Washington State regulators, and Oregon and Washington universities describing. At the table, too, was John Walker, a key EPA central office powerhouse who had provided the funding to build professional capacities. Topics at this workshop included the 1991 background on the establishment of the Northwest Biosolids Management Association (NBMA), its governance, its priorities for professional networking, its programs for public outreach, its research priorities and its involvement in regulatory development. The target audience for the workshop was biosolids leaders from California, the Southeast, the Northeast and the Mid-Atlantic regions. Attendees received a compelling collection of sample bylaws, budgets, job descriptions, and action plans – everything they would need to start new regional associations of their own. The Mid-Atlantic region was represented by four individuals. These included folks from a public agency, an NGO and two service companies.

This is a screenshot of the June 11, 1997, opening of the networking workshop hosted by the Northwest Biosolids Management Association in support of expanding regional biosolids associations.

This formative networking meeting in June 1997 would prove instrumental in what came next in the founding of MABA. Two months later, the first week of August 1997, the WEF Residuals and Biosolids Conference, organized jointly with the American Water Works Association, was held in Philadelphia. The call went out for “A Meeting for Mid-Atlantic Residuals and Biosolids Stakeholders” on August 5, 1997, at noon, and Pete Machno was again at the center of this new meeting, with his leadership role as chair of the committee that had several years prior coined the term “biosolids,” helping attract a national audience of biosolids practitioners to this first meeting in the mid-Atlantic. The first name on the sign-in sheet was Pete Machno’s. Thirty-one others signed below him. Of those, 11 would go on to play an active role in the formation of an interim board, four would go back to their other regions to organize, and two were from the regulator community. Notably missing were representatives of a group that was so important to the NBMA, the agricultural researchers.

Ours is a professional community that commits and stays committed, even in the face of a lot of stuff, such as PFAS. Of the 32 at the table in Philadelphia in 1997, eight are still active biosolids practitioners in the MABA region today, 28 years later. At Northwest Biosolids Biofest this year in September 2025, several familiar faces who were there at the start of NBMA in 1991 are still attending, notable personalities like Chuck Henry, Mike Van Ham, Dan Thompson and Kyle Dorsey. Maile Lono-Batura, the longest standing association leader, reported from this year’s Biofest that Henry, Van Ham, Thompson and Dorsey regard the strong and positive collaboration of operators, farmers, scientists and regulators as the reason they have remained engaged over the decades.

A stakeholder meeting was held in Philadelphia on August 5, 1997, two months after the networking workshop, during a lunchtime interlude of the WEF/AWWA joint residuals conference, with Pete Machno presiding during the conversation that would yield MABA and support NEBRA.

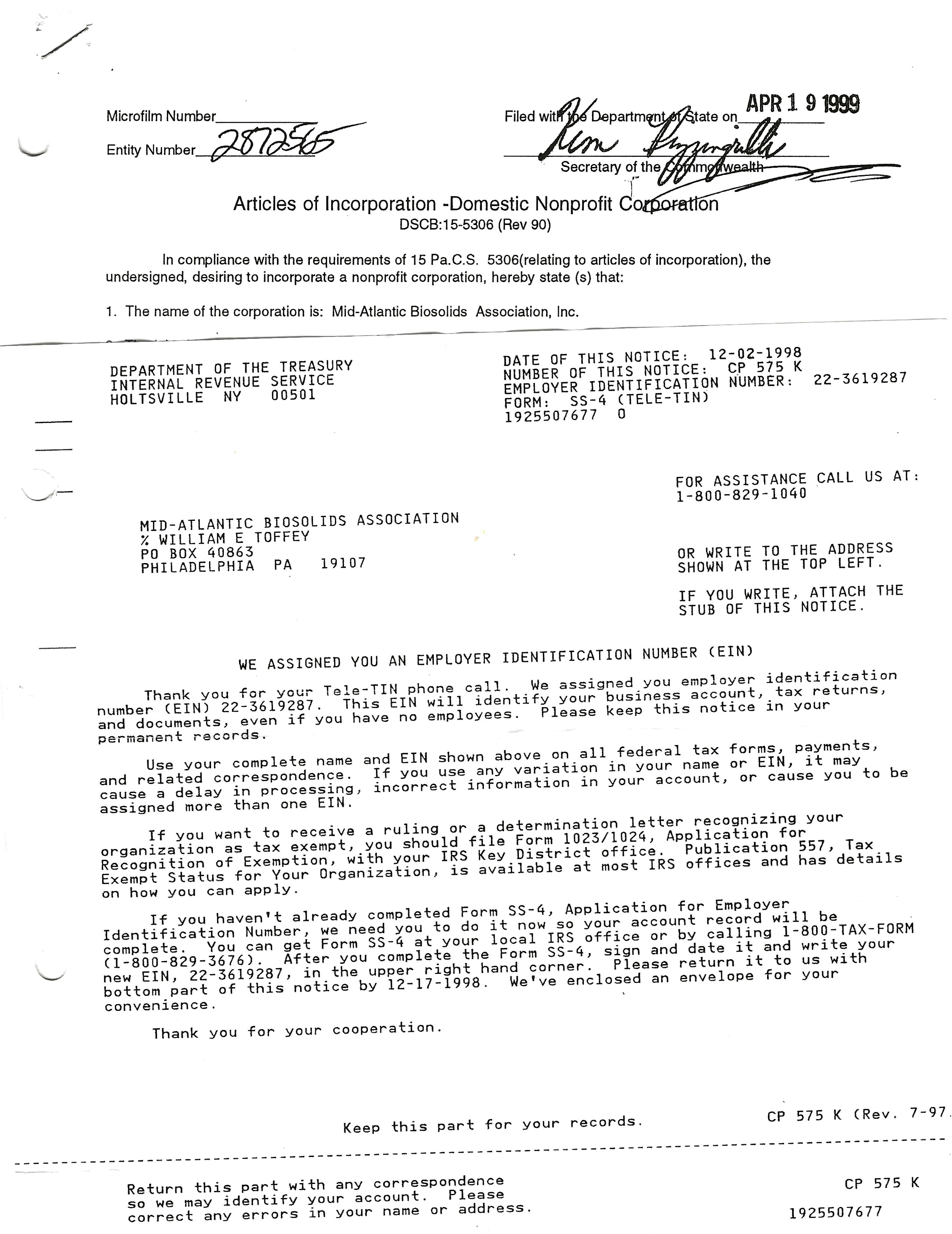

During the 16 months following that “stakeholders” meeting, an enormous amount of organizational progress was made. The stakeholders, chaired by Steve Gerwin (WSSC Water), made the essential decision to establish an organization comprised of organizational members, in contrast to individuals, from public and private generators and service companies as voting members, but other environmental groups and regulators as non-voting members. The region served ended up as the states covered by EPA Regions 2 and 3, though it originally did not extend north to New York nor south to Virginia. The founding stakeholders group, which numbered as many as 34, took on the task of creating the original bylaws and articles of incorporation (guided by Bill Toffey and Jane Forste), the key decision points being the membership classes and the size and representation balance on board of trustees. The stakeholder group also appointed a nominations committee (led by Barbara Petroff) to recommend members for the first board and first officers, with the understanding that these positions would be designated “interim” until “incorporation” had been completed.

The first organizing meeting of the MABA stakeholder was held on January 7, 1998, with strong attendance and assignment of roles to cover all aspects of association building.

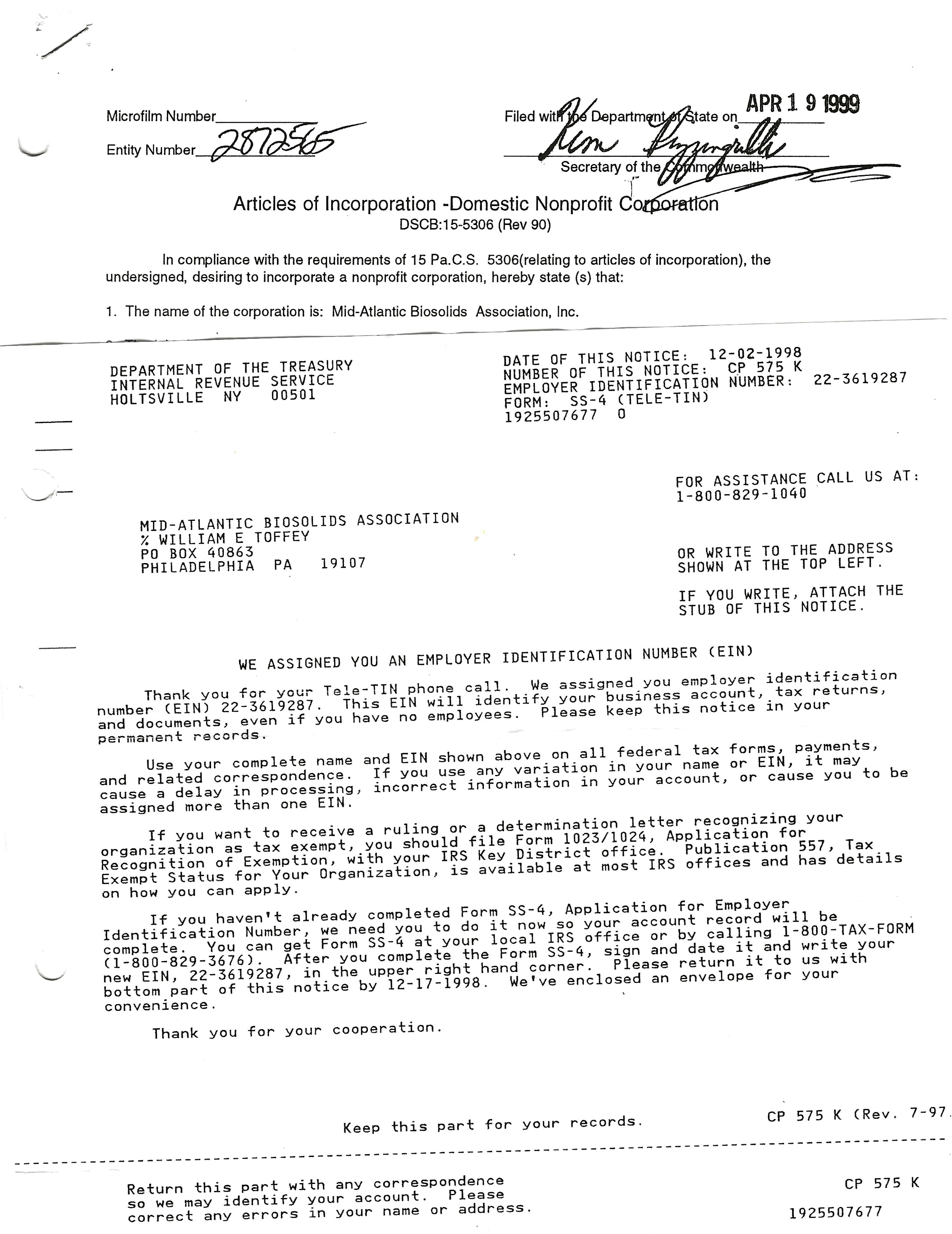

All things considered, the stakeholders group moved quickly. This progress was summarized in a presentation made by Toffey at the NJWEA annual conference in May 1998 (Evolution of the Mid Atlantic Biosolids (Management) Association). The nominations committee of the stakeholders group went forward to recommend a slate of board members and officers, approved by unanimous consent at its meeting on July 23, 1998, with Bill Toffey elected President, even though he was absent from the meeting. The establishment of the board and officers was then proudly announced to our growing list of biosolids contacts. With a board and officers in place, the application to the IRS for a tax identification number was submitted in September, and on 12-2-1998 the IRS came forth with an EIN.

To promote the regional association initiative, Bill Toffey made a pitch to the largest WEF Member Association in the region, the NJWEA annual conference, in May 1998

One of the early sticking points had been the new organization’s name. The agenda of the first three stakeholders meetings in 1998 included discussions on the name. The sticking point was the word “Management.” Did the term have a sufficiently inclusive connotation, or was it best left out of the name to embrace more inclusivity. At the meeting of May 2, 1998, the stakeholders were still in a deadlock. What better way to break the impasse than a coin toss. With the toss of the coin the new organization became the Mid Atlantic Biosolids Association. Thereby, papers could be completed and the application to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for incorporation could be filed, with now four elected officers as signatories. The Pennsylvania Department of State provided official acknowledgement of the Mid-Atlantic Biosolids Association, Inc., as a Domestic Nonprofit Corporation on April 19, 1999. Twenty-two months following the Seattle “Investing in Success” workshop, biosolids practitioners in the mid-Atlantic region were in full operation.

By the end of the year, the state incorporation documents and the federal tax number assignments had been received, which opened up a path to bank accounts, websites and other tangible organization tools.

Second on the sign-in sheet in that August meeting, just under Pete Machno’s signature, was Steve Gerwin. Gerwin had attended the workshop in Seattle and had soaked in the vision put forth by Machno’s team and by Walker, and he was ready to drive the formation of MABA straight out of the gate. “We needed to be out front with the public to make our case for biosolids and become effective communicators with the public and news media,” recalls Gerwin, who was at that time leading biosolids projects for Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission, now WSSC Water. His drive and leadership skill resulted in his selection as chair of the stakeholders group from its first meeting. After completing his time as WSSC Water, Gerwin joined Howard County Bureau of Utilities, and then retired to Florida, enthusiastically providing leadership in local issues, having remarried after being widowed.

Gerwin had brought along to the August gathering his Maryland colleague Al Razik, an engineer with Maryland Environmental Services (MES), who was managing the solids of a dozen facilities and confronting odor problems, regulatory uncertainty and public resistance. Razik recalls it being “excited to meet other biosolids managers from around the Mid Atlantic to discuss the issues we were all facing.” Razik jumped in with a career-long volunteering for MABA, having continued to serve today through his retirement from MES as MABA’s treasurer.

Barbara Petroff had also attended the workshop in Seattle and brought back the NBMA vision to her contacts on the East Coast. Petroff is a person with a natural talent to enroll people in collaborations and with instincts to organize action. At that moment in summer 1997, her role with US Filter was marketing the IPS Composting System, yet she found time to lead both the ad hoc bylaws and nominations committees. “Networking came easy to me,” Barbara explains today. In her persuasive conversations with Guru P. Bose, the manager of the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) biosolids management unit, Petroff convinced Bose to have his staffer Bill Toffey, PWD’s Utilization Manager, spend considerable time developing the emerging organization. With that understood, Petroff and Gerwin deftly arranged for Toffey to be elected President of the nascent board in a move that also elected 21 board members.

If there was one person responsible for Toffey’s move into a career of biosolids it was Diane Garvey. Garvey had started out as a graduate engineer in PWD’s Sludge Management Unit when Toffey, as a city environmental planner, first engaged with the city’s unfolding biosolids program in the 1980s. In 1997, now as a consulting engineer, Garvey assumed biosolids leadership as chair of the state association’s biosolids committee and had been cochair of the WEF residuals conference. Garvey’s was the third name on the sign-in sheet at the August 5 meeting. She had been impressed at the innovative research and the level of operator training that the NBMA was providing and saw that as a gap in the mid-Atlantic that needed to be filled. She didn’t see the state member association doing that. This was a viewpoint shared also by Trudy Johnston, at the time an engineer with Gannett Fleming, and for long now with Material Matters. Looking back, Johnston recalls: “PWEA was old, farty and backwards and was stopping us from promoting biosolids.”

A national biosolids leader like Garvey, Mark Lang, a biosolids consultant in New York and New England, also attended the August meeting, already strongly committed to regional associations. He saw them as holding promise for effective outreach, as he had reluctantly abandoned his effort to have WEF invest in a national advertising campaign for biosolids using “remnant ad” inserts. “I still see our regional associations as key for public and media outreach. I believe the PFAS issue is an opening for us to explain wastewater and biosolids treatment to the public,” Lang says today.

Whether it was competition or collaboration, the North East Biosolids and Residuals Association (NEBRA) was out in front of MABA by several months in getting itself organized. Shelagh Connelly had just recently formed her own residuals service company, White Mountain Resource Management, Inc., and was pregnant with her second child when she was invited to attend Machno’s June workshop in Seattle. She was very impressed by the commitment in the Northwest to a collaborative approach to research and outreach. On her return to her New Hampshire offices, she assigned her staffer Ned Beecher the responsibility for participating in NEBRA’s organization. Connelly also came to the Philadelphia stakeholders meeting, bringing along with her several of the emerging NEBRA leadership, including Carolyn Jenkins (NEIWPCC), Amy Barad (MWRA) and Ginny Grace (NEFCO).

Connelly sees the project started in 1997 in generational terms. She has never regretted cultivating enthusiasm among young employees. “The best thing for me is looking out during the meetings today and seeing the large number of young women. Felicia Morrissette started with me and I am so proud to see her success with NEFCO, and now to see her role in setting up the Southeast Biosolids Association. We were launched (in 1997) and now we launch the next generation,” Shelagh asserts boldly today.

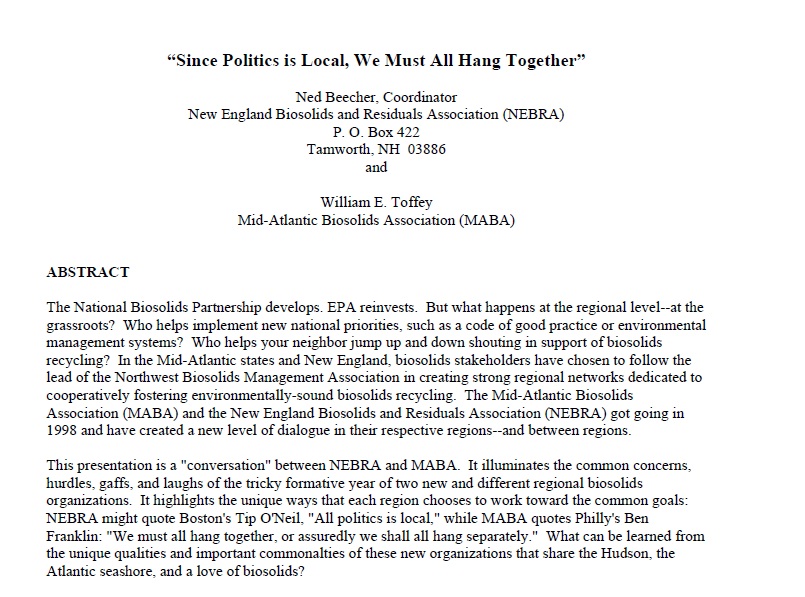

As we know now, Beecher would go on to become director of NEBRA, and Toffey, after his career at PWD was complete, would become director of MABA. But back in 1998, when it was all so new, Beecher representing NEBRA and Toffey representing MABA, made a joint presentation to the WEF Residuals and Biosolids Conference in 1999 on progress so swiftly made with setting up the two regional associations. In their paper, “Since All Politics is Local, We Must Hang Together,” they finished with a vision for the organizations as “clearing houses and communications hubs, assisted by the power of emerging communications and computing technologies… learning to overlook differences, finding common ground, and ‘hanging together.’”

At the occasion of Northwest Biosolids 35th anniversary, Maile Lono Batura welcomed Bill Toffey, Ned Beecher and Greg Kester (CASA) to express the fun part of regional biosolids associations.

Twenty-seven years later, we are doing this in spades.

In their joint “vision” Beecher and Toffey concluded: “And it is all fun, because we all have enough time to devote to it, because these efforts are all well-funded.”

Well, at least part of that vision came true.

For more information, contact Mary Baker at [email protected] or 845-901-7905. |

|

|

August 2025 - MABA Biosolids Spotlight

Provided to MABA members by Bill Toffey, Effluential Synergies, LLC

SPOTLIGHT on Land Reclamation

Residuals with a Rhythm in Pottsville

“American Green has settled into a rhythm,” Tim Chronister explains. After all, twenty-three years have passed since the Reading Anthracite company in Pottsville, Pennsylvania, the owner of American Green Corporation, received its first truckloads of biosolids from the city of Philadelphia Water Department for reclamation of its mine lands, among the largest holdings in the Commonwealth. While many “lessons learned” followed from those first deliveries, the regulatory requirements set by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and enforced by the Pottsville Regional Mining Office, have remained mostly the same over the years. As this mining district’s exclusive user of biosolids for reclamation, American Green sees a “rhythm” as a very good thing. The operational rhythm includes, importantly, a one-time surface application rate of 60 dry U.S. tons of biosolids per acre over several tons per acre of lime, incorporated with multiple passes of large harrows. Following incorporation, Chronister says the “prescribed seeding mix,” that mix first developed with the input of the legendary Dr. William Sopper of Penn State, an advocate for biosolids use from the 1970s, has consistently provided a dependable vegetative cover for biosolids application sites. “The very old reclamation sites are still largely open, and that has provided for a good landscape feature for wildlife,” Chronister notes.

American Green’s Tim Chronister applied and incorporated 60 dry tons of biosolids on the resculpted mine surface of this anthracite mine late last Fall in eastern Pennsylvania, and a rich vegetated cover has become established in just two months after a March sowing.

For most of this generation-long program of reclaiming active mine sites within Reading Anthracite’s some 40,000 acres of landholdings, American Green’s offer to the biosolids community has been as an open door, available very nearly year-round, even during periods of dire weather. “Customers” have included principal biosolids service companies, private wastewater operators, and municipal agencies within an affordable reach, as far away as a day’s truck drive. A recent new offering by American Green includes its own fleet of dump trailer trucks for biosolids hauling services, the company’s response to unpredictability of contractors. Over the past two decades, American Green has tested several “bright ideas,” including several years of deep row trenching with hybrid poplars, blending biosolids with papermill residuals, trial plots of a variety of hardwood tree plantings, plantings of bioenergy crops such as switchgrass, and operation of a livestock ranch. With today’s PFAS issues confronting the industry, thought has been given to raising crops on reclamation lands that would be suitable for conversion to PFAS absorbents. But the backbone of it all for American Green is traditional surface application at reclamation rates, building on its access to specialized heavy duty land moving equipment customarily used in mining.

American Green recognizes that the opportunity to beneficially recycle biosolids to disturbed mine sites will continue to be an attractive option to agricultural uses in an unsettled regulatory arena where the ultimate shape of PFAS and phosphorus restrictions remains uncertain. As Chronister said, a good rhythm is a great answer to today’s risks.

Mobile Class A Biosolids

“Every man needs a hobby,” modestly comments Greg Barchey of Denali Water Solutions. If any single person in Pennsylvania can be credited with keeping the flame alive for biosolids recycling on mine lands, it is Barchey, and he has a long history to prove it. As a college student in 1980, Barchey attended a community meeting of angry citizens opposing Modern Earthline’s hauling of Philadelphia stuff 250 miles west to bituminous coal mining sites in Somerset County, Pennsylvania. Barchey showed up at the company’s local headquarters soon after and was pretty much offered a job on the spot. “I thought it was the coolest thing.” He figures that now, 45 years later, he has overseen over 10,000 acres of reclamation: “It has been a rollercoaster, of ups and downs, straight over and over, but the good that has been done on land that would have never been reclaimed is amazing, and it will last forever.” Along with a dependable field hand Philip Will, Barchey has been the one constant in a story line that involves a string of such companies as Spectraserve, Hydropress, Mobile Dredging, and then his own company Kyler Environmental. As Kyler’s singular biosolids entrepreneur, Barchey developed a mobile lime stabilization rig that could make a Class A lime stabilized product at a mine site location, and for this system he received a special PaDEP permit for its operations. The uniqueness of this operation had WeCare Organics buy out Kyler, provided he would stay on, and so he did, even when WeCare’s operation was folded into Denali Water.

Denali’s Greg Barchey deploys mobile equipment of his design at a recently completed bituminous coal mine in western Pennsylvania, providing a Class A level of stabilization with alkaline materials to produce a low odor and unfailingly successful soil amendment for reclamation.

The “hobby” part is Barchey’s signal that he is satisfied that his Denali “bosses,” specifically including such energetic young blood as Ryan Cherwinksi (see Ryan’s profile in the SPOTLIGHT on Young Professionals in the MABA Region in May 2025). Denali and Cherwinski are content with letting Barchey manage a “hobby” scale operation of approximately 500 acres of annual reclamation that comprises the current demand in this coal region. In addition to the work on active mine sites required for release of bonds benefitting the mining companies, Denali has also returned to sites at which conventional revegetation had failed, using an “agronomic” rate of biosolids, far lower than the full reclamation rate, to the benefit of the state’s Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation overseeing old mine sites. Yet, Barchey and Cherwinski agree that the “politics” have not gotten better from the early days of biosolids reclamation decades ago, although the mobile Class A stabilization system, with no skimping on the rate of alkaline materials used in the process, helps ensure a biosolids product with little of the pungent odor that had given offense in the past.

One attribute that joins Barchey and Cherwinski together is their joy seeing the results on the landscapes. Cherwinski enthuses: “it is a no-brainer, it is so visual; such a perfect fit, when you take a moonscape and turn it into a meadow, with a beneficially used product like biosolids, and with a 100 percent success rate.” His operators have seen a bear with a cub. He has witnessed a herd of elk wintering on the fields. Hunters have been won over by the dependable deer populations that migrate to the reclaimed fields at the edge of the woods. Local wastewater agencies will find Denali’s sites an easy outlet. As for public concerns, Cherwinski does not flinch from the upset residents who show up, remaining respectful of their concerns and urging them to witness the environmental benefits. “I try to show them it is about the soil. We need to rebuild the soil.”

Manufactured Topsoil in Vermont

“I wanted a job after I graduated,” Mary “Lulu” Cook, environmental engineer at Cold River Materials (CRM), casually explains about her “capstone” research as an intern. The research project was applying scientific principles to optimizing a manufactured topsoil (MFT) from a blend of superfine rock dust and organic residuals. The rock dust is drawn from a settling pond used during the production of aggregate materials through rock crushing and washing. Organic residuals are supplied by Resource Management Inc. (RMI), a residuals services company in New Hampshire, in the form of carbon-rich ash from biomass energy production and lime stabilized biosolids.

Cook’s major in environmental science at Franklin Pierce University in New Hampshire had brought her to intern work at CRM. She was introduced to a project begun by sustainability manager Juli Simons at VINCI Construction USA, part of a global construction enterprise, of which CRM is a subsidiary. Simons had formulated a soil blend she devised with RMI’s assistance to help establish a grass cover for dust suppression along internal roadways and work areas. The viability of MFT as a replacement for the customarily prescribed, but scarce, natural loam on construction projects was questioned. Simons needed proof that MFT was preferred to loam as a medium for dust suppression. She also saw potential for the use of MFT for reclamation and green space improvements if she could objectively demonstrate its performance. Cook saw this need for scientific proof as an opportunity to marry her work for CRM to the capstone requirements of Franklin Pierce University’s environmental science program, while showcasing her skills and interest as a potential employee.

Cook applied statistical and agronomic research rigor to her study. She set up four 1,000 square foot plots, to create 4 treatments: MFT/Kentucky bluegrass, MFT/conservation mix, traditional loam/Kentucky bluegrass, and traditional loam/conservation mix. The MFT was a one to five volumetric ratio of organic residuals and rock dust. Soil consultant Andrew Carpenter analyzed the MFT, showing that, though low in organic matter, it was high in pH due to the high lime in both the wood ash and the biosolids, also with ample micronutrients and sulfur. The native loam soil is typically borrowed from riparian zones of farm fields and has a pH of 5.5 to 6, and its use robs the environment of an important soil resource. The application rate of each soil type was 4 to 6 inches. During the growing season, the plots were watered to ensure 1 inch of water weekly. Over the growing season, Cook sampled all subplots for both the percentage of vegetative cover and for fresh weight biomass.

A field research demonstration project, conducted by Lulu Cook while a senior at Franklin Pierce University, showed the effectiveness of a manufactured topsoil (MFT) for dust-suppression and attractive vegetation at the Vermont aggregate company VINCI Construction.

The results were conclusive. The MFT outperformed the loam soil. The strong results are expected to support approval of the material for use on construction projects by state departments of transportation. Cook’s study was submitted by CRM to VINCI Construction’s global environmental competition for demonstration of the circular economy. On VINCI’s Environment Day September 24th, the MFT project was one of nine awards. What is more, Lulu Cook graduated successfully and got her job, naturally.

Bringing Clean Air to Princeton, BC

“I returned to Princeton (British Columbia (BC)) last year, and you can’t even tell this was a mine 30 years ago -- that’s why I enjoy reclamation work,” Curtis Navratil explains. As a senior project manager for SYLVIS, the pre-eminent residuals firm in western Canada, Navratil manages several SYLVIS reclamation projects in the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta. But one of the earliest and most memorable projects in his career took place at Copper Mountain near Princeton, BC, 170 miles east of Vancouver.

Navratil started with Metro Vancouver (formerly the Greater Vancouver Regional District (GVRD)) in 1994 just as the Similco Copper Mine, now named the Copper Mountain Mine, was gearing up to undertake reclamation of a settling pond known as the Grandby Tailings, a pond that nestled along the Town of Princeton. At the time, strong winds blowing off the ponds would put down a layer of dust daily throughout the town. Applying biosolids to the site created a vegetative cover that dramatically reduced dust emissions, improving local air quality. The project was so successful that the British Columbia Lung Association presented GRVD with an award for significantly improving air quality and public health by reducing dust. This award remains one of Navratil’s proudest achievements.

Metal and coal mine sites in western Canada are arid and windblown, making the kind of effective reclamation carried out by Curtis Navratil of SYLVIS Environmental Services with biosolids products necessary to avoid adverse environmental health impacts.

Today, Navratil applies his thirty years of reclamation expertise in using biosolids to several coal mine closures across western Canada. Biosolids from the City of Edmonton, Alberta, are being used to reclaim the 31,000-acre Highvale sub-bituminous coal mine, no longer supplying a coal-fired electric generator. Also in Alberta, the Sheerness Coal Mine, with 17,000 acres under reclamation, faces a topsoil deficiency in meeting reclamation standards across 1,600 acres. Biosolids compost from the City of Medicine Hat, supplemented with manure compost, are being supplied to help meet reclamation standards. The Boundary Dam lignite coal mine in Estevan, Saskatchewan, likewise has a shortage of topsoil, compelling this province’s first biosolids-based reclamation -- 960 acres starting in 2024 with biosolids from the City of Estevan. Over the past two decades, Navratil has also worked on a copper mine in Logan Lake, BC, a gold mine in Hedley, BC, and an aggregate mine in Sechelt, BC, along with several other coal mines.

Work has restarted at the Copper Mountain Mine, now under ownership by Hudbay Minerals, which is planning to double copper production. Elsewhere in western Canada SYLVIS blends biosolids with other residuals including wood waste and rock fines to make amendments to “kickstart” soil development. Most of the mineral mines in western Canada are conventional open pit operations, with truck and shovel activity, not dissimilar to Eastern Pennsylvania’s anthracite mining, but with unique challenges. The region’s arid climate limits water availability and leaves the sites vulnerable to wind-driven erosion of the tailings ponds and rock faces. In many cases, there is often insufficient soil or overburden to meet reclamation requirements – and the material that is available lacks fertility, organic matter, and structure.

For more than 35 years, SYLVIS has researched, recommended and implemented biosolids-based reclamation and restoration to address these challenges. Biosolids are a valuable tool to support soil development and sustain the ecosystem services a healthy soil provides. SYLVIS continues to refine reclamation strategies to establish vegetation and improve site aesthetics, ensuring that reclaimed mines not only meet regulatory standards but also deliver long-term environmental benefits.

For more information, contact Mary Baker at [email protected] or 845-901-7905. |

|